Amid all the hoopla about the entry-level wage (a.k.a., the minimum wage) one question is often left unanswered: Who exactly earns the entry-level wage?

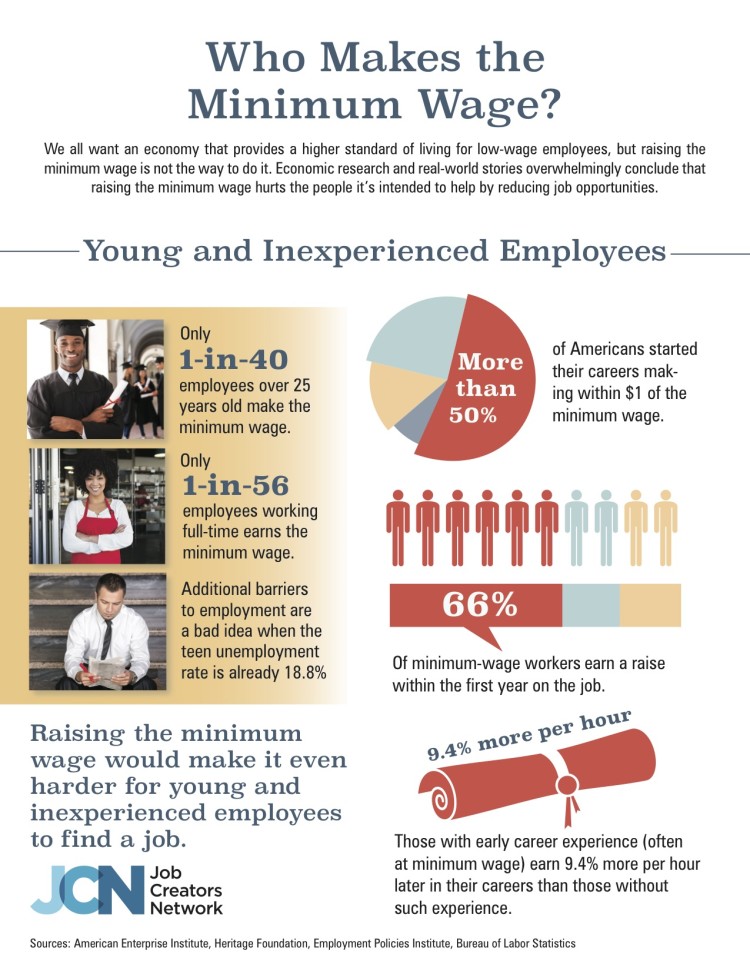

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has the answer. In 2015, more than 78 million workers age 16 and older were paid at hourly rates, representing almost 60 percent of all wage and salary workers. Among those paid by the hour, roughly 870,000 employees earned exactly $7.25 an hour—the federal entry-level wage. That’s just 1.1% of hourly workers and a fraction of one percent of all workers. And employees under the age of 25 made up about half of the entry-level workforce.

The 1.1 percent of employees earning an entry-level wage represents the lowest percentage in the last five years. That number has dropped consistently since 2010, shortly after the last federal wage hike was phased in midway through 2009. (For perspective, the percentage hovered around 13 percent in the late 1970s.)

This suggests it doesn’t take long for those earning an entry-level wage to move up the career ladder. According to the Heritage Foundation, two-thirds of entry-level employees earn a raise within their first year on the job. When given an opportunity, employees quickly acquire the skills and experience they need to advance in their careers—making entry-level work a crucial stepping stone for once-inexperienced workers.

But raising the entry-level wage to $15 an hour—as California and New York have done already—reduces job opportunities by making employees significantly more expensive. This imposes higher labor costs on job creators—who are often forced to cut back on hiring job-seekers—hurting the very people such policies are intended to help.

A better way forward is expanding the Working Americans Credit (WAC)—also known as the Earned Income Tax Credit—which doesn’t cut off entry-level opportunities and actually helps those in need. The WAC directly supplements employees’ incomes through the tax code without increasing labor costs. It operates on a sliding scale, meaning that employees earning less money or with more children to support qualify for a higher tax credit. This means the WAC’s pay-out decreases as earnings rise—redirecting the tax credits to those who need them most.

Policymakers should prioritize entry-level work opportunities to jumpstart young people’s careers—not get rid of them.